Election News Email Dump Twist

Wednesday, November 2, 2016 at 10:24AM

Wednesday, November 2, 2016 at 10:24AM

Integrity in Journalism - Is There any Truth?

Close Relationship of Hillary & Huma

Is a story about a lesbian first lady ever true?

They read at first blush like the plaints of a lovelorn schoolgirl. “Oh dear one,” begins a letter dated 1933. “It is all the little things, tones in your voice, the feel of your hair, gestures, these are the things I think about and long for.”

Goes another when the two were apart: “Hick darling. Oh I want to put my arms around you. I ache to hold you close. Your ring is a great comfort. I look at it and think, she does love me, or I wouldn’t be wearing it.”

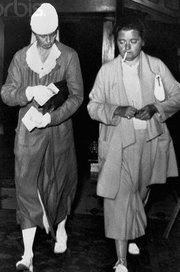

These newly released billets-doux were, in fact, written on White House stationery by Eleanor Roosevelt. They have suddenly ignited a sizzling scholarly debate about their author’s relationship with the woman they were addressed to: a salty, cigar-smoking, stoutly built reporter named Lorena Hickok.

As author Doris Faber reveals in her 1979 book, The Life of Lorena Hickok, the journalist and the President’s lady were an odd couple but a close one. They exchanged 3,360 letters in a correspondence that began in 1932 and ended with Eleanor’s death three decades later. Large numbers sound familiar? - like 3,360 Roosevelt letters verses 600,000 Clinton emails? Of course, there are Hillary-Huma private emails expected in that mix too.

Forty years have passed since Doris Faber uncovered, to her frank dismay, incontrovertible evidence at the F.D.R. - Roosevelt Library that Eleanor Roosevelt had once been in love with another woman, a crackerjack Associated Press reporter named Lorena Hickok. The two women had exchanged more than 3,300 letters that survive—we’ll never know how many more Hickok destroyed due to their explicit nature.

Forty years have passed since Doris Faber uncovered, to her frank dismay, incontrovertible evidence at the F.D.R. - Roosevelt Library that Eleanor Roosevelt had once been in love with another woman, a crackerjack Associated Press reporter named Lorena Hickok. The two women had exchanged more than 3,300 letters that survive—we’ll never know how many more Hickok destroyed due to their explicit nature.

Like much of the early scholarship surrounding the Roosevelt-Hickok relationship, “The Life of Lorena Hickok” (1980), the book that resulted from Ms. Faber’s discovery, suffered from a did-they-or-didn’t-they prurience in keeping with Reagan-era squeamishness about AIDS and gay issues generally. It fell to Blanche Wiesen Cook to dispel Victorian prudery and sensationalism alike. Ms. Cook’s game-changing work is rightfully acknowledged by Susan Quinn in “Eleanor and Hick,” her poignant account of a love affair doomed by circumstance and conflicting needs. Combining exhaustive research with emotional nuance, Ms. Quinn dives deep to convey the differing characters of president and first lady. Confronted with the pending divorce of their daughter, Anna, Eleanor encourages the younger woman to escape an unhappy marriage. FDR, by contrast, urges caution, reminding her that many couples “got on very well in the end without love.”

By her own admission, Eleanor Roosevelt fought a lifelong battle against fear, the fear of being unloved most of all. It was a vulnerability she was quick to recognize in others. Enter Lorena Hickok, Hick to her friends and colleagues. Raised in rural South Dakota, she survived a nightmarish childhood with an abusive father who, not content to beat his animal-loving daughter, dashed a favorite kitten’s brains against the barn. Taught “never to expect love or affection from anyone,” Hick was 13 when her mother died. Within a year she was sent packing by the dead woman’s replacement. Taking refuge in books and music, she found work, at age 19, as a cub reporter on a Battle Creek, Mich., newspaper. There she impressed editors with her versatility, humor and sensitivity toward outcasts of every stripe. In Minneapolis and Milwaukee she covered sports as authoritatively as a society ball. By 1932 the sole woman reporter on Franklin Roosevelt’s presidential campaign train, Hick concluded of the candidate’s wife: “That woman is unhappy about something.”

Her journalist’s intuition served her better than her journalist’s detachment. Before Election Day, Hickok had been given a privileged glimpse into the unorthodox Roosevelt marriage—into Eleanor’s “special friendship” with a handsome New York state trooper named Earl Miller; and Franklin’s intimate attachment to his longtime personal secretary Missy LeHand. All this Hick kept secret, along with FDR’s long-ago betrayal of his marital vows—and her own growing attachment to the tall, vulnerable woman who trusted her discretion.

“Remember,” Eleanor told Hick shortly after becoming first lady, “no one is just what you are to me.” By then Hick had quit the AP, trading her career for a fantasy life to be shared exclusively with her new love. For her part, ER plotted ways to escape the White House, traveling—more or less—incognito with Hick through Canada and on the West Coast. When, inevitably, their identities were uncovered, Hick’s former colleagues were not kind in their descriptions of her girth, appetite or bruising manner. Sufficient hints were dropped to feed suspicions about the first lady’s unconventional attachments.

Eventually, Eleanor’s ardor cooled. Needing to be needed, she couldn’t bear the thought of being possessed. “You have a feeling for me which I may not return in kind,” she told Hick in 1935. Deeply wounded, Hickok took to the road as a semiofficial diarist of the Great Depression.